Naltrexone is a medication that directly counteracts the intoxicating effects of legal and illegal opioid narcotic substances. Doctors sometimes use the medication to treat people recovering from opioid addiction, but the success of this treatment depends largely on each individual taking his or her naltrexone dose on a regular basis.

In a study published in March/April 2014 in the American Journal on Addictions, a team of Chinese researchers explored the safety of a long-lasting, injectable form of naltrexone that could eliminate some of the concerns about maintaining regular dosing of the medication.

Naltrexone For Opioid Addiction Treatment

Scientists classify naltrexone with a group of substances known as opioid antagonists. When they enter the bloodstream, all of these substances travel to the sites that normally give opioid drugs and medications access to the brain. Once they reach these sites, opioid antagonists physically block opioids and prevent them from producing their narcotic effects.

Scientists classify naltrexone with a group of substances known as opioid antagonists. When they enter the bloodstream, all of these substances travel to the sites that normally give opioid drugs and medications access to the brain. Once they reach these sites, opioid antagonists physically block opioids and prevent them from producing their narcotic effects.

Naltrexone, in particular, can play a role in opioid addiction treatment because it blocks the effects of opioid substances, lowers the level of opioid craving in recovering addicts and helps diminish the chances that recovering opioid addicts will relapse.

Unlike two opioid-based medications—called methadone and buprenorphine—commonly used in opioid addiction treatment, naltrexone is not a controlled substance. This means that doctors and other qualified health professionals require no special licensing to prescribe it. Many health professionals prescribe an oral form of the medication that patients must take every day.

Injectable Naltrexone

Extended-release, injectable naltrexone is also known as depot naltrexone. Doctors or other qualified professionals administer this medication directly into muscle tissue (typically the gluteus muscles). Instead of dissipating in the bloodstream relatively rapidly like oral naltrexone, extended-release, injectable naltrexone gradually enters the bloodstream for roughly one month and blocks access to the effects of opioid drugs and medications throughout that time.

The main potential benefit of this form of naltrexone is improved compliance with the abstinence goals established in opioid addiction recovery programs. Like the short-acting oral version of the medication, depot naltrexone can trigger severe withdrawal symptoms if given to a recovering addict who still has opioids in his or her system.

For this reason, standard treatment guidelines stipulate that doctors wait at least a week after the verified end of opioid intake to administer the medication. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the sale of an extended-release, injectable naltrexone product called Vivitrol in 2010.

Safety Of Injectable Naltrexone

In the study published in the American Journal on Addictions, researchers from three Chinese institutions used a small-scale trial to assess the safety of injectable depot naltrexone and examine patients’ ability to tolerate the medication.

All told, this trial included 36 people. Twenty-four of these individuals participated in a separate panel. Six people in this panel received a relatively high 400 mg dose of injectable naltrexone, while another six received a relatively low 200 mg dose of the medication. Twelve people in the panel received placebo injections that mimicked either the 400 mg naltrexone dose or the 200 mg naltrexone dose. The remaining 12 study participants were enrolled in a second panel and randomly received either six monthly 400 mg naltrexone injections or placebo injections that mimicked the naltrexone injections.

The researchers found that both the recipients of the 200 mg injections and the 400 mg injections still had medically significant amounts of naltrexone in their bloodstreams one month after dosing. Eleven of the people who received injectable naltrexone had some sort of adverse reaction while using the medication.

The researchers concluded that seven of these reactions were potentially the result of naltrexone exposure; however, they also concluded that none of the observed reactions produced moderate or severe effects.

Overdose Risks?

The authors of the study published in the American Journal on Addictions found that extended-release naltrexone injections deliver steady amounts of the medication for a minimum of one month. They also found that the medication does not accumulate dangerously after multiple monthly injections occur.

Overall, they concluded that extended-release, injectable naltrexone is tolerated well by patients and does not pose any undue safety risks.

On a related note, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration points out that fatal or non-fatal opioid overdoses sometimes occur in people who receive monthly naltrexone injections but still continue taking opioid substances; however, the same overdose risks also apply to users of oral naltrexone or opioid-based treatment options.

If You Or Someone You Love Is Struggling With Addiction, Call Us Now! Help Is Waiting.

See Why Naltrexone Helps Reduce Amphetamine Use Could This Be An Effective Treatment For Your Addiction?

Addiction to opioid drugs, like heroin, is a terrible disease and one that is difficult to overcome. Even with the best treatment and addiction professionals, coming clean from opioids and staying clean is a huge challenge. The impact that these drugs have on the brain and the body is so strong that it takes a major effort to stop using them. For this reason, researchers have worked on developing medications to help addicts. One such drug is Suboxone and it can help heroin and other opioid addicts stay sober. However, as an opioid itself, this medication can also be abused.

Withdrawal Symptoms Of Opioids

One of the main reasons quitting opioid drugs is so difficult is the severity of withdrawal symptoms. Taking addictive drugs repeatedly leads to changes in the brain. An addict needs the drug simply to feel normal again. When an opioid addict goes off his drug, he will experience anxiety, agitation, insomnia, achiness, sweating and a runny nose in the early stages. As withdrawal progresses, the symptoms get worse and include cramps, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms are extremely uncomfortable and lead many addicts to start using again.

What Is Suboxone?

Suboxone is a drug with active ingredients called buprenorphine and naloxone. Together these ingredients reduce the symptoms of withdrawal from opioid drugs. When an addict gets relief from the terrible symptoms of withdrawal, he is more likely to stay sober. There are a few risks associated with taking Suboxone, and potential side effects such as cold-like symptoms, sweating and headaches.

Suboxone is a drug with active ingredients called buprenorphine and naloxone. Together these ingredients reduce the symptoms of withdrawal from opioid drugs. When an addict gets relief from the terrible symptoms of withdrawal, he is more likely to stay sober. There are a few risks associated with taking Suboxone, and potential side effects such as cold-like symptoms, sweating and headaches.

Suboxone has been proven by research to be effective in helping opioid addicts stay clean. In one study, nearly half of the addicted participants using Suboxone were able to reduce their use of narcotic opioid painkillers. The success rate dropped to below 10 percent when the participants stopped using Suboxone.

How Is Suboxone Able To Be Abuse?

Although it is an opioid, just like narcotic painkillers and heroin, Suboxone’s impact on the brain is much less than the more addictive drugs. However, there is still the potential for abuse. Another opioid that has been used to treat heroin addicts for decades, methadone, has a much greater potential for abuse than Suboxone. As a result, methadone is tightly controlled. Suboxone can be prescribed in a doctor’s office and the addict can take it home. This more lax approach to dispensing Suboxone leaves the door open for abuse.

Overdose And Death From Suboxone?

Furthermore, because regulations are not as tight as with methadone, many users don’t realize that it is possible to overdose and die from taking too much Suboxone.

Recent reports in the news illustrate the problems associated with Suboxone. Although it can help addicts get clean, it is clear that some people are abusing it and using it to get high rather than to stay sober. In New York, people have been arrested recently for trying to sell Suboxone. Not only are addicts being prescribed the drug abusing it, it’s also entering the illicit marketplace and being sold to non-addicts looking for a high. Arrests have also been made in Virginia and other states.

Drugs like Suboxone are important for helping people who desperately want to stop using heroin and other opioids. However, no error-free drug has yet been developed. As long as there is any possibility of getting high on a medication, the drug will be abused by someone. Doctors need to take great care in prescribing these medications and policy makers must consider whether restrictions need to be tightened to prevent further abuse.

Read More About Buprenorphine Treatment For Opioid Addiction

Self-reporting of drug use is an approach that uses interviews, questionnaires or surveys to determine whether a person uses drugs, has previously used drugs or currently has drugs in his or her system. This method differs from objective urine testing, a universally accepted approach that relies on chemical measurements to detect the presence of drugs. In a study published in October 2013 in the journal Addictive Behaviors, a team of researchers from several U.S. institutions compared the accuracy of self-reported drug use by teenagers and young adults in drug treatment to the accuracy of urine testing. The researchers found that individuals in these age groups tend to self-report their level of drug use with relatively consistent truthfulness.

Self-Reporting Drug Use

Drug treatment professionals and researchers use self-reporting to gather a range of statistics from small and large populations of drug users. Examples of the information commonly acquired include the absence or presence of drug use, frequency of drug use, larger patterns of drug use and the presence of underlying factors that may contribute to drug use frequency or drug use patterns in some way. Depending on the scope of an interview, survey or questionnaire, self-reporting may provide data on short-term drug usage, annual drug usage or lifetime drug usage. Some professionals and researchers use self-reporting to answer relatively simple questions about drug usage, while others use the technique in connection with complex formulas designed to gather very specific, detailed information from participants.

Urine Drug Testing

Urine drug testing is a specific form of urinalysis designed to detect the presence of commonly abused substances such as opioid narcotics, marijuana and other forms of cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine and phencyclidine (PCP). In some cases, urine testing directly detects the presence of these substances; in other cases, it detects the breakdown products that these substances form after entering the bloodstream. A urine drug test only tells the person conducting the test whether an individual has used a particular substance within a narrow time span of roughly one to three days. It does not provide information about such factors as the method of drug use, the specific moment of drug use or the amount of drugs taken at a given time. Testers typically confirm the results of a urine drug test with a follow-up testing procedure designed to guarantee the final accuracy of the rendered results.

Accuracy Of Self-Reporting On Drug Use

Because urine drug testing provides an objective measurement of drug use, experts in the field commonly view this form of testing as the standard tool for detecting the presence of drugs in a person’s system. However, in certain situations, it is not necessarily convenient or practical to perform urine testing. In addition, the proper interpretation of testing results is sometimes relatively complex and time-consuming. For these reasons, doctors and other professionals sometimes have a real need for other ways of obtaining the information they require.

In the study published in Addictive Behaviors, researchers from three U.S. universities sought to determine if self-reporting of drug use can act as a reliable substitute for urine drug testing. They explored this question with the help of 152 teenagers and young adults enrolled in programs primarily geared toward the treatment of addictions to opioid narcotic drugs. Some of the participants received short-term (two-week) treatment with group/individual counseling and a standard combination of two opioid addiction medications called buprenorphine and naloxone. Others received longer-term (12-week) treatment with counseling and the combination of buprenorphine and naloxone. Self-reports and urine testing results were obtained from each group at regular intervals. Each participant received a small financial reward as an incentive to keep participating in the study.

After completing the study’s main phase, the researchers concluded that the teens and young adult participants provided self-reported information on drug use that generally matched up well with the objective measurements provided by urine drug testing. Generally speaking, these findings were unaffected by factors such as the amount of money received for participation and the specific nature of each individual’s drug addiction. However, the study’s authors also concluded that teens and young adults who received longer-term counseling and medication treatment had a greater tendency to under-report their drug use than teens and young adults who received shorter forms of treatment. Specifically, these individuals downplayed their involvement in both opioid and cocaine use.

So Is Self-Reporting Accurate Enough For Solo Drug Testing Use?

The authors of the study published in Addictive Behaviors believe that their findings demonstrate that teens and young adults in treatment commonly self-report their drug use accurately enough to give doctors a potential secondary alternative to urine drug testing. However, they also believe that the level of accuracy is not high enough to do away with the need for urine testing, especially in teens and young adults participating in relatively long-term treatment programs. And Save Your Life Or The Life Of A Loved One

Get Drug Rehab Counseling Help Now And Save Your Life Or The Life Of A Loved One!

People addicted to opioid narcotics (and other drugs of abuse) often have additional mental health issues that significantly complicate their recovery during addiction treatment. In many cases, the situation is worsened by recovering addicts’ relatively infrequent use of available psychiatric services. In a study published in November 2013 in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, researchers from Johns Hopkins University assessed the usefulness of an approach called contingency management (CM) in increasing recovering opioid addicts’ willingness to participate in psychiatric treatment. The researchers found that appropriate use of contingency management can significantly boost program participants’ attendance for psychiatric services.

Opioid Addiction And Mental Illness

Like other forms of drug and alcohol addiction, opioid addiction is officially classified as a form of mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association. This is true because continued, excessive use of addictive substances literally alters the function of the human brain, and thereby fosters a range of serious, dysfunctional changes in everyday behavior. In addition, opioid addictions (and other substance addictions) often appear at the same time as other forms of diagnosable mental illness such as depression, schizophrenia or anxiety disorders.

Like other forms of drug and alcohol addiction, opioid addiction is officially classified as a form of mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association. This is true because continued, excessive use of addictive substances literally alters the function of the human brain, and thereby fosters a range of serious, dysfunctional changes in everyday behavior. In addition, opioid addictions (and other substance addictions) often appear at the same time as other forms of diagnosable mental illness such as depression, schizophrenia or anxiety disorders.

Numerous factors help explain the overlap between addiction and these mental illnesses, including the ability of substance abuse/addiction to trigger the onset of additional illness and the ability of non-substance-based mental illnesses to increase the risks for involvement in substance use. Research also indicates that substance addiction and other forms of mental illness share several important common risk factors that increase their likelihood of appearing together.

Contingency Management Basics

Contingency management is a behavior modification technique that uses rewards (and, in some cases, punishments) to bring about desired results in a drug treatment program or other therapeutic setting. One common form of this approach, called voucher-based reinforcement or VBR, uses the distribution of vouchers for services or material goods to encourage treatment compliance.

Another form of CM, called prize incentives contingency management, motivates compliance by giving patients a chance to win cash with every significant step toward active treatment participation. Contingency management is used in programs that treat addiction to substances such as opioid narcotics, marijuana, amphetamine, methamphetamine, alcohol and nicotine. Some programs use the technique to encourage abstinence during the course of recovery. Others use it to encourage participation in the psychiatric programs that address other forms of mental illness in people involved in substance addiction treatment.

Addicts Willing To Remain In Drug Rehab With Contingency Management

In the study published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, the Johns Hopkins University researchers used an assessment of 125 adults going through outpatient treatment for opioid dependence to gauge the effectiveness of contingency management in improving the willingness to receive psychiatric services during participation in an addiction recovery program. Half of these individuals received $25 vouchers for each week of full participation in a 12-week course of psychiatric treatment. The remaining adults had access to the same psychiatric treatment, but did not receive vouchers or any other form of reward for treatment attendance. The researchers measured each group’s level of attendance after each month of the program.

After reviewing their findings, the researchers concluded that, compared to an approach that doesn’t employ contingency management, use of voucher-based CM nearly doubles the level of psychiatric treatment attendance after one month of treatment. In addition, use of vouchers more than doubles the level of attendance after two months of treatment and after three months of treatment. People who receive vouchers for psychiatric services remain in opioid addiction treatment just as often as people who don’t receive vouchers. They also successfully avoid using opioid drugs with equal frequency.

Contingency Management’s Clear Benefits In Addiction Programs

The authors of the study published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence believe that the use of contingency management techniques provides clear benefits for encouraging the use of psychiatric services in opioid addiction programs. However, they note that their research only looked at psychiatric services delivered to patients in a purposeful, coordinated manner during the course of addiction treatment.

Services delivered in other ways may or may not receive the same attendance boost from the contingency management approach. The authors also note that the specific type of psychiatric treatment offered in any given program may have a considerable impact on the usefulness of CM. In addition, program managers may need to alter or modify their use of CM in order to meet the specific challenges faced by their patient clientele.

Read More About Drug Rehab Treatment And Contingency Management

20 Sep 2013

Understanding Opioid-Related Disorders

Opioid-related disorders is the collective name of a group of substance-related disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a reference guide commonly used by mental health professionals across America. All of the conditions with this name involve negative consequences associated with the use of a wide variety of opioid narcotic medications or drugs. DSM 5, the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, makes several changes to the definitions of the opioid-related disorders. Some of these changes involve a mere change in wording, while others involve a significant change in meaning.

Opioid-Related Disorder Basics

The five opioid-related disorders listed in DSM 5 are opioid use disorder, opioid intoxication, opioid withdrawal, “other” opioid-induced disorders and “unspecified” opioid-related disorder. Opioid use disorder is a new condition created by blending the definitions for two other conditions, called opioid abuse and opioid dependence, which appeared in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual’s” obsolete fourth edition (DSM IV). Opioid intoxication and opioid withdrawal keep the same definitions they had in DSM IV. The “other” opioid-induced disorders heading is a substitute for five separate DSM IV conditions. “Unspecified” opioid-related disorder acts as a substitute for a loosely defined DSM IV disorder called opioid-related disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).

Opioid Use Disorder

Opioid drugs and medications are well known for their ability to trigger substance abuse in users, as well as substance dependence (a medical term for addiction). People affected by substance abuse don’t meet the criteria for diagnosing a physical/mental addiction, but still participate in ongoing substance-based behaviors that strongly impact their lives in negative ways. People affected by substance dependence do meet the criteria for diagnosing an addiction; like substance abusers, they also participate in clearly harmful substance-based behaviors on a regular basis.

Issues of substance abuse and substance dependence overlap to a considerable degree. In fact, from a scientific standpoint, it’s perfectly reasonable to view dependence as a particularly damaging form of abuse. DSM IV kept the diagnosis of substance abuse and substance dependence strictly separated. However, DSM 5 discards the separate listings contained in DSM IV and establishes a replacement condition—called substance use disorder—which joins the symptoms of substance abuse with the symptoms of substance dependence. In accordance with this change, opioid users with significant abuse- or dependence-related problems will now receive a single diagnosis for opioid use disorder.

Opioid Intoxication

People in the midst of opioid intoxication develop at least two symptoms that alter their normal mental function, change their behavior for the worse, or otherwise impede their ability to carry out their typical routines. In all cases, one of the symptoms present must be unusual narrowing or widening of the pupils. Other qualifying symptoms include an inability to pronounce words properly, unusual sleepiness, a decline in normal memory function, a decline in the ability to voluntarily focus attention, and the onset of the dire state of unresponsiveness known as a coma. Additional requirements for a diagnosis include verifiable use of an opioid drug or medication in the very recent past and lack of other psychological or physical issues that could produce the problems attributed to opioid use.

Opioid Withdrawal

Opioid withdrawal occurs when an opioid user who has grown accustomed to the effects of a drug or medication suddenly stops using that drug or medication, or steeply decreases use over a short span of time. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual provides doctors with guidelines to gauge the seriousness of withdrawal in any given patient. People going through grade 0 opioid withdrawal typically develop symptoms such as anxiety, a strong desire to continue drug/medication use, and the presence of behaviors designed to fulfill that desire. People going through grade 1 withdrawal develop symptoms such as unusual sweat output, uncontrollable yawning and unusual tear or mucus production. Symptoms associated with grade 2 opioid withdrawal include twitching muscles, restricted eating patterns similar to those found in people with anorexia, and pupil dilation. Grade 3 opioid withdrawal symptoms include sleeplessness, cramping abdominal muscles, muscle weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, and abnormal increases in blood pressure, heart rate and breathing rate.

“Other” And “Unspecified” Disorders

The “other” opioid-induced disorders diagnosis is designed to describe the presence of any mental disorder-related symptoms that appear as a consequence of opioid use. It replaces five separate diagnoses contained in DSM IV, including opioid-induced mood disorder, opioid-induced sleep disorder, opioid-induced sexual dysfunction, opioid-induced psychotic disorder with delusions, and opioid-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations. The “unspecified” opioid-related disorder diagnosis lets mental health professionals identify cases of opioid-related mental health problems that don’t meet the minimum requirements for diagnosing any other opioid-related disorder.

When people are afraid to get on an airplane, friends may comfort them by saying that many more people die in motor vehicle accidents than in airplane crashes. It seems incomprehensible to think that someone could say, “And even more people die by suicide.” But according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), that is, in fact, the case.

In a recent issue of the CDCs Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the number of people who died in motor vehicle accidents in 2010 was listed at 33,687, while the number of people who committed suicide was 38,364. Researchers noted that the majority of Americans taking their own lives were in the baby boomer generation. Economic problems, easier accessibility to opioids and stresses caused by care-giving are just some of the suspected causes of the suicide increase in this generation.

Suicide rates climbed most alarmingly in the baby boomer generation. In the 10-year study period, women in their 60s had a 60 percent increase in suicides (eight per 100,000) while men in their 50s had a 50 percent increase (27 per 100,000).

Researchers speculate on multiple reasons for the spike in the suicide rate. Baby boomers are arriving at reflective ages where some of them are not satisfied with where they are in their life. Life’s pressures and problems seem to prove too much for some.

Multiple problems and pressures may be pushing the American suicide rate higher. Financial loss or strain is just one possible reason for a feeling of hopelessness that may lead to suicide. Researchers believe that other problems may be caused by the overuse and easy accessibility of prescription painkillers. Opioid addiction is also rising in this country.

Being a caregiver for an aging parent while also taking care of a child who has returned home after college can also take a toll on boomer parents. While that age group is supporting family both older and younger than themselves, who is supporting them?

CDC representatives stress that the suicide rate may decline if more prevention programs and support is offered to those at risk for suicide. Sometimes it is not just one of the above mentioned problems or pressures—it is a combination. These complex reasons can be better sorted out with the guidance of professionals

Not only should at-risk individuals be helped, but so should those who have lost a loved one to suicide. Support groups to help those survivors can help the next generation learn to live through the pain and not give up hope in their own lives.

Read More About Opioid Abuse And Suicide Risks

17 Mar 2013

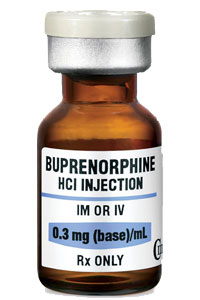

Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Addiction

Buprenorphine is a relatively weak opioid medication that doctors sometimes use to treat addictions to stronger legal and illegal opioids such as oxycodone (OxyContin), codeine, and heroin. Like other opioids, buprenorphine achieves its effects in the body by attaching to specialized sites on nerve cells (neurons) throughout the body called opioid receptors. However, it produces much smaller mind-altering effects than commonly abused opioids, and people recovering from addictions to those drugs can use buprenorphine to gradually transition through the withdrawal process, rather than going through severe withdrawal symptoms. In order to reduce any risks for inappropriate use, some forms of buprenorphine come combined with another drug called naloxone.

Buprenorphine is a relatively weak opioid medication that doctors sometimes use to treat addictions to stronger legal and illegal opioids such as oxycodone (OxyContin), codeine, and heroin. Like other opioids, buprenorphine achieves its effects in the body by attaching to specialized sites on nerve cells (neurons) throughout the body called opioid receptors. However, it produces much smaller mind-altering effects than commonly abused opioids, and people recovering from addictions to those drugs can use buprenorphine to gradually transition through the withdrawal process, rather than going through severe withdrawal symptoms. In order to reduce any risks for inappropriate use, some forms of buprenorphine come combined with another drug called naloxone.

Read More

07 Mar 2013

Opioid Use and Driving Impairment

Opioids (also known as opiates or narcotics) are a class of drugs used legally for pain relief and cough reduction, and also used illegally for their ability to produce a form of intense pleasure known as euphoria. They achieve all of these effects by binding to nerve cells (neurons) in the central nervous system and altering the signals produced by those cells. People who have grown accustomed to the effects of properly used prescription opioids typically experience no real reduction in driving skills. However, people unaccustomed to properly used opioids, as well as people who abuse prescription or illegal opioids, can develop a number of serious driving impairments.